Norma, by Vincenzo Bellini – La Monnaie, 28 December 2025

Norma is a druidic priestess in Roman-occupied Gaul. She sings to the Moon in the famous aria Casta diva, officiates nocturnal ceremonies in the forest, and serves as an oracle of the ancient gods. Her sacred prophecies call for peace, even as everyone around her longs to rise up against the Romans and sing loudly about it.

Yet Norma, the purest and highest of priestesses, harbours more than one scandalous secret – and has very personal reasons for wishing peace with the occupiers. Pollione, the Roman proconsul, is her lover. Together they have had two children, hidden away in the forest. Norma’s feelings toward these illegitimate children are deeply conflicted: she fears for their future should they be discovered, even to the point of contemplating killing them or sending them to Rome with their father – anything rather than seeing them enslaved.

Norma has broken the law and betrayed her god. Matters worsen when Pollione decides to elope with Adalgisa, a younger and rather naïve priestess. Their love duet (Vieni in Roma) is among the opera’s finest moments. Norma is furious – heartbroken, yet perceptive enough to recognise Adalgisa as Pollione’s latest victim, and she vows to protect her. Adalgisa, having realised that Pollione is a liar and a womaniser, refuses to leave with him. The two women forge a powerful bond through a series of beautiful duets (even if it sometimes sounds as though they are singing from different planets).

Eventually, when Pollione refuses to return to Norma and attempts to abduct Adalgisa against her will, Norma strikes the gong and calls the tribe to war. Pollione is captured, but Norma cannot bring herself to sacrifice him. Instead, she confesses her crime of fraternising with the enemy. In a final act of inexplicably renewed love, both are consumed together on the pyre. Their orphaned children are entrusted to their grandfather, Oroveso, the head of the tribe (Alexander Vinogradov), who ends the opera in shock at his daughter’s confession and self-immolation. This sets the stage for a majestic final chorus and a thunderous conclusion.

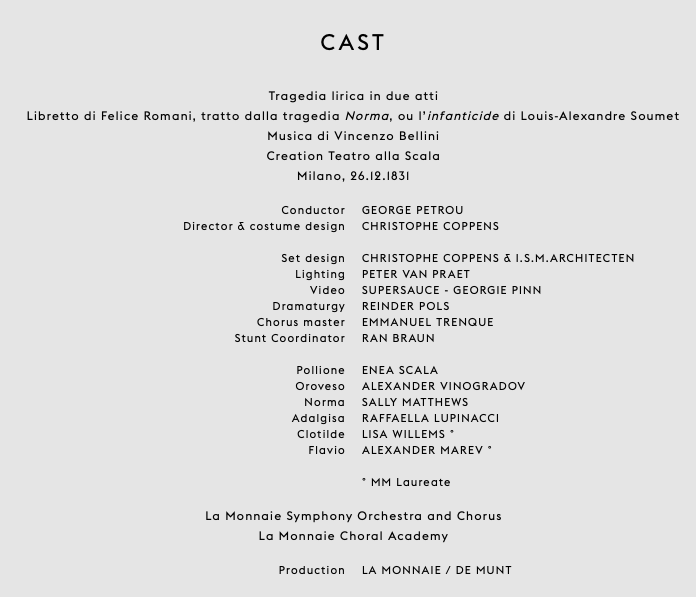

This production was originally planned for the 2020–2021 season and was partially cancelled due to the Covid pandemic. Now, five years later, much of the cast has remained the same. Sally Matthews sang Norma, Enea Scala was Pollione, and Raffaella Lupinacci – whom I had already heard in Monteverdi last season – was an excellent Adalgisa.

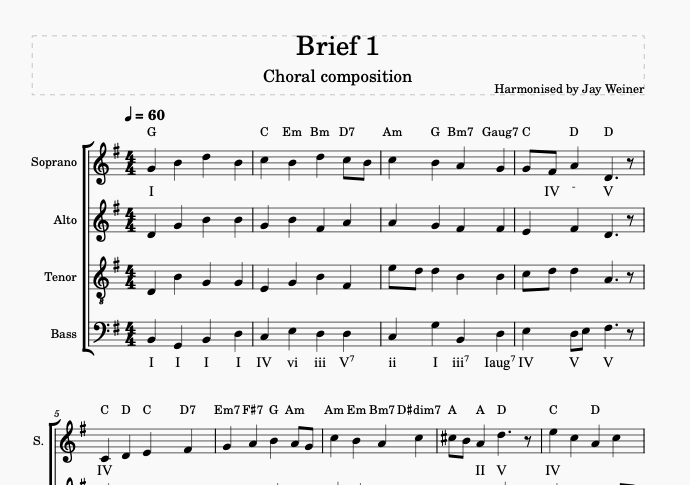

Norma is an exceptionally demanding role and a defining example of bel canto, a style focused on the beauty of the melodic line and rich ornamentation (essentially the musical language of Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini). Norma’s opening aria-cavatina, Casta diva, was originally conceived for a voice of some depth, capable of agility in the upper register – such as a coloratura mezzo or a dramatic soprano with flexibility and a secure high C. This is why the role has traditionally been sung by sopranos. Maria Callas’s legendary interpretation, with its added embellishments and high notes, set a tradition that still shapes expectations today. I was therefore hoping for a true diva—but unfortunately, there was none.

On the evening I attended, Sally Matthews did not fully convince as Norma. Some of the high notes were missing, her voice sounded tired, and the balance felt strange – especially since the mezzo sounded clearer and higher by comparison. Given that Norma is the longest role and dominates the stage for much of the opera, constantly duetting and joining ensembles, this was a real disappointment. The tenor also struggled with intonation, though the strength of the bass and mezzo performances largely saved the evening.

The orchestra and chorus of La Monnaie, however, sounded wonderful under the direction of George Petrou.

The most disappointing aspect – aside from the weak Norma – was the staging, sets, and costumes. The stage felt empty, the acoustics suffered, and the story of Druids, Romans, and female solidarity was lost in a setting resembling a car park, complete with street fights and absurdly omnipresent vehicles. I generally enjoy modern productions, but this one crossed the line into the ridiculous.

Opinions from critics

- ‘Norma fait monter ses pneus neige’ à la Monnaie – Céline Dekock and Nicolas Blanmont- Musiq3

- Car Park Casta Diva – Nigel Wilkinson – Parterre Box

- Norma à la Monnaie : Pollione et les ferrailleurs – Benedict Hévry – Res Musica

- Norma à La Monnaie dans le rétroviseur du XXIe siècle – Soline Heurtebise – Ôlyrix

- BELLINI, Norma – Bruxelles – Dominique Joucken – Forum Opera

- À la Monnaie, la Norma de Christophe Coppens roule des mécaniques – Olivier Vrins – Crescendo Magazine

Leave a Reply