Can You Hear What The Elf King Is Whispering in My Ear?

Singing characters and conveying emotions in Baroque and Romantic songs and arias

Jay Weiner, soprano – S7ENB – EEB1 Pre-Bac, January 2026

The human voice, produced entirely by the body, is arguably the first musical instrument and remains one of the most direct and powerful vehicles for emotional expression. Unlike external instruments, the voice is inseparable from the physical and psychological state of the performer: it is shaped by breath, posture, muscle coordination, imagination, and emotion in real time. This intimate connection gives vocal sound a uniquely immediate impact on listeners, allowing emotions to be communicated with urgency and authenticity. Across cultures and historical periods, the voice has functioned not only as a carrier of language but as a primary means of expressing feeling, identity, and social connection. Its importance predates formal music-making and even spoken language, suggesting that vocal sound lies at the foundation of human communication.

Long before the emergence of complex speech, vocalisation played a crucial role in human survival. Early humans relied on sounds to signal danger, coordinate group activity, and maintain social bonds. High-pitched vocalisations in particular are known to trigger strong emotional responses linked to care, protection, or alarm, as exemplified by infant crying. Such responses appear to be deeply biological, bypassing rational thought and acting directly on the nervous system. This may explain why high voices are often associated with vulnerability, innocence, or supernatural beings in music and drama, from Baroque angels to Romantic children and spirits.

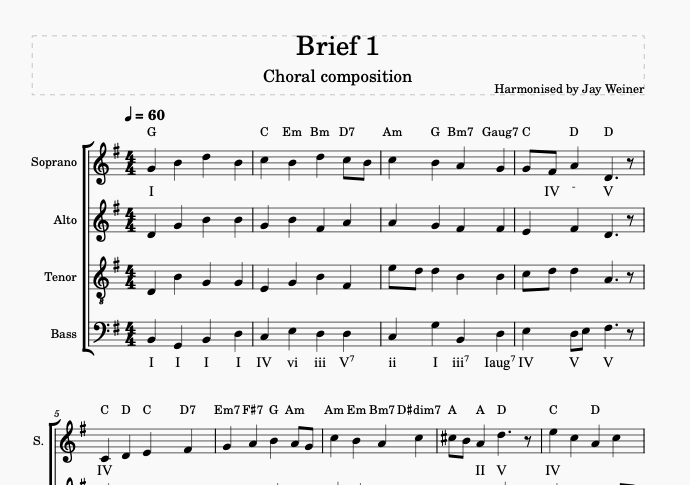

As a singer with experience in a boy soprano register, I have developed my vocal practice through opera, musical theatre, and choral work. These genres situate the voice within a dramatic framework shaped by conductors, directors, staging, costumes, and narrative. Emotional expression is supported and intensified by text, action, and visual elements, aligning with Richard Wagner’s concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork, in which multiple art forms combine to convey maximum meaning and emotional impact.

By contrast, performing art songs and operatic arias in recital or audition settings removes much of this external dramatic support. The singer stands still, often in concert dress, with minimal gesture and no interaction with other characters. In this context, the full responsibility for emotional communication rests on the voice alone, supported only by the piano. The Lied is often described as “singing an opera in three minutes,” which gives an idea of the concentration of narrative, character, and emotion required. In preparation for auditions to UK conservatoires, I therefore constructed a programme of contrasting pieces chosen for their theatrical potential and suitability to my voice. Through musical, textual, and historical analysis, guided by a music coach, I aimed to maximise expressive impact. This essay draws on that analytical process, elements of which will be presented in the school pre-baccalaureate concert.

Audition requirements vary significantly between conservatoires, with some insisting on Italian opera, others on English repertoire, and most requiring stylistic and emotional contrast. In all cases, candidates must demonstrate versatility in mood, tempo, language, and historical period. I therefore explored a wide range of repertoire, including Baroque arias, Romantic Lieder, French opera, and contemporary works, many of them written for young characters or high voices, or able to be sung in multiple registers.

I selected four contrasting pieces: Purcell’s Music for a While, Schubert’s Erlkönig, Stéphano’s aria « Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle ? » from Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, and Oscar’s aria « Saper vorreste » from Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. Together, these works span over two centuries, four languages, and a wide emotional range, while for the most part sharing a common focus on youth, innocence, and heightened emotional states. In this essay, I will focus primarily on Music for a While, Erlkönig, and Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle ?, as these pieces illustrate most clearly the challenges of characterisation and emotional communication in non-staged vocal music.

I. Music for a While

Henry Purcell’s Music for a While occupies a unique position in the English Baroque repertoire. Originally composed as incidental music for John Dryden’s play Oedipus, King of Thebes, it functions dramatically as a lullaby sung to pacify Alecto, one of the Furies, so that the dead king Laius may be summoned back to life. The paradox of soothing a violent, supernatural creature through gentle music lies at the heart of the piece’s potential in expressiveness.

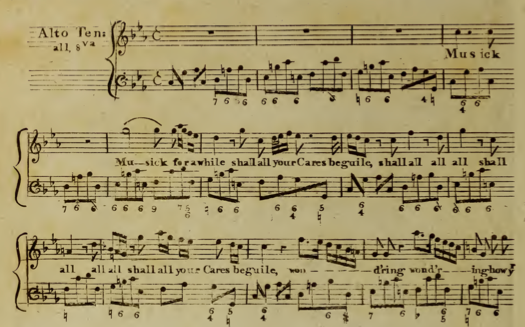

Musically, the song is built over a basso ostinato – a repeating bass line that ascends step by step, often interpreted as symbolising the gradual ascent of the dead from the underworld. Above this hypnotic foundation, the vocal line unfolds in long, irregular phrases, with frequent chromaticisms and subtle dissonances. Purcell makes extensive use of word painting, a characteristic Baroque technique, most famously on the word “drop,” where descending intervals illustrate the snakes falling from Alecto’s head. The result is music that feels both calm and uncanny, suspended between sleep and danger.

One remarkable aspect of Music for a While is its adaptability to different voice types. Originally intended for a high male voice (countertenor or boy treble), it has been performed and recorded in at least nine different keys, ranging from low baritone versions to very high soprano interpretations. This flexibility reflects historical performance practice, in which transposition was common to suit available singers. After listening to numerous recordings, I chose to perform the piece in G minor (despite the most common soprano register being Am), a key that allows me to sustain the long legato phrases without too much trouble while preserving the intimacy and darkness of the original.

Interpretatively, the main challenge lies in maintaining a seamless vocal line over the repetitive bass, without becoming static or monotonous. Breath control is crucial, as phrases often extend beyond the natural breathing points suggested by the harmony. Stylistically, the piece demands restraint, elegance, and clarity of English diction. Emotionally, the singer must convey calm authority and hypnotic persuasion rather than overt drama. The goal is not to express personal emotion, but to embody the power of music itself as a force capable of taming chaos. For me, this piece represents a neutral emotional starting point in the programme: serene on the surface, yet charged with underlying tension.

My favourite interpretation of Music for a While – and the excerpt I chose for it – is that of Andreas Scholl, a countertenor who specialises in baroque music. He performs the piece like how it would have been sung and orchestrated when it was written and has a clarity and purity to his voice that i find necessary to truly get across the soothing nature of the piece, while maintaining a lightheartedness and airiness, notably in the “drop drop drop” section, with his rolled Rs and short notes.

II. Erlkönig

If Music for a While demonstrates the Baroque ideal of controlled affect, Schubert’s Erlkönig represents the Romantic fascination with psychological drama, nature, and the supernatural. Composed in 1815 when Schubert was only seventeen or eighteen, this setting of Goethe’s poem was his first published work and remains one of the most demanding and dramatic songs in the repertoire.

The poem tells the story of a father riding through the night with his feverish child, who is tormented by visions of the Erlking (elf king), a supernatural figure who lures and ultimately kills him. Uniquely, the song requires a single singer to portray four distinct characters: the narrator, the father, the child, and the Erlking. A fifth “character,” the galloping horse, is vividly depicted in the piano accompaniment through relentless, fast triplets that persist almost uninterrupted until the final bars.

Although often performed by baritones, Erlkönig was originally written for a high voice, which is particularly effective in conveying the child’s terror. For me, the greatest challenge of the piece lies in rapid character changes, sometimes within a single phrase, while maintaining musical accuracy at a fast tempo. Each character requires a distinct vocal colour: the narrator neutral and detached, the father low, calm, and authoritative, the child increasingly high and agitated, and the Erlking seductive, smooth, and sinister.

Language and diction play a crucial role. German consonants and vowels must be clear enough for the audience to follow the narrative, especially in a concert setting without subtitles. Facial expression and minimal gesture also become essential tools for differentiating characters. Emotionally, the singer must balance technical control with raw intensity. The child’s repeated cries of “Mein Vater!” should sound genuinely panicked, while the Erlking’s promises must initially appear gentle and alluring before revealing their violent intent.

The title question of this essay—“Can you hear what the Elf King is whispering in my ear?”—comes directly from the child’s perspective in the poem. In performance, my aim is to make the audience experience the story through the child’s ears and fear, even if they cannot see the supernatural threat. When the final line reveals that the child is dead, the emotional impact depends entirely on the singer’s ability to sustain tension until the very end.

I’ve chosen three extracts of Erlkönig to cover, each from the singer i believe suits each of the characters the best. That is – Hermann Prey’s Father, Dietrich Fischer Deskau’s Elf King, and Jessye Norman’s Son and Narrator.

Dietrich Fischer Deskau’s performance of the piece in its entirety is my favourite overall, but i think his voice and manner are best suited to his portrayal of the Erlking in particular. When he first “morphs” into the character, he appears to unfocus his gaze and ever so subtly maintain a grin on his and a twinkle in his eye, making the Erlking’s first words sound like somewhat subdued musings through a nearly blank stare. Halfway through this first intervention however, Fischer Deskau suddenly shifts his wideeyed gaze in the direction of the audience, displaying a much more intense, and intentional look, accompanied by a now less hidden grin . Throughout the rest of the section he holds ‘eye contact’ as the Erlking presumably with the boy, and in watching, the viewer truly feels the eeriness of the character and how creepy the monster is. This agility in facial expression accompanied by Fischer Deskau’s clarity of voice, and mastery of nuances creates in the audience that same sense of muddled fear and fascination that the boy would be feeling in that very moment.

Hermann Prey’s interpretation of the father feels particularly adequate due to his bass-baritone register, and the deep, grounded colour of his voice. He performs the father’s sections with heavy – and appropriate – contrast to his interpretations of the other characters, displaying him as authoritative but caring for his child. Visually, he sustains a mainly neutral expression, but always tilts his head downward and looks up through his eyebrows, and keeps his hands raised reassuringly, ready to hold his child closer. After the boy’s section, when the father reassures him there are no monsters, Prey also slightly takes his time on those words, for the father to appear calmer for his child.

For the child, I felt Jessye Norman’s performance was the most fitting, thanks to her high voice which most accurately portrays the cries of a scared child. Norman maintains an exaggerated but adequately intense look of pure fear throughout her sections as the son, especially in his last intervention, right before his death (which is part of the excerpt i chose), and she uses a lot of body language such a shaking and swaying, and leaning over before the narrator’s conclusion to the piece, which she delivers more coldly, getting across the weight and finality of the kids death, most apparent in her delivery of the last line (“was dead”), which she almost whispers.

III. Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle?

In contrast to the dark intensity of Erlkönig, Stéphano’s aria from Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette offers a playful yet provocative portrayal of youthful bravado. Stéphano, Romeo’s page, is a “trouser role,” traditionally sung by a mezzo-soprano or soprano. Although the character does not appear in Shakespeare’s original play, he serves an important dramatic function in the opera by provoking the Capulets and escalating the conflict.

The aria alternates between a recitative and a lively, mocking song. Stéphano compares Juliet to a white dove trapped among vultures and teases the Capulets with ironic warnings that she will escape them. Musically, the piece requires agility, clear French diction, and a bright, youthful tone. Rapid changes of tempo and character mirror the shifting emotions of the text, from lyrical description to sarcastic challenge.

For me, the challenge lies in balancing vocal brilliance with characterisation. The aria must sound light and spontaneous, never heavy or aggressive. High notes and quick passages should convey confidence and youthful insolence rather than technical effort. Emotionally, the piece introduces humour and irony into the programme, demonstrating a different kind of expressive skill: the ability to communicate joy, mischief, and provocation with clarity and charm.

The excerpt I chose for this piece, and my favorite performance of it is Anat Czarny’s. I find that she portrays the character with a playful dignity that is sometimes lost in interpretations of him, and her vocal technique is flawless, perfectly executing the contrasts between stern and lighthearted sections. I also particularly like how she’s staged in this production, with her looking in one direction for the Capulets, and in another for the Montagues.

The primary objective of this audition programme was to gain acceptance into one of the highly competitive conservatoires in London, which admit only a small percentage of applicants. As a singer several years younger than the average candidate, with a voice still in development, I could not rely solely on vocal power or maturity. Instead, I aimed to demonstrate musicality, stylistic awareness, linguistic accuracy, and, above all, the ability to convey emotion and character.

Detailed knowledge of the historical and musical context of each piece proved essential, both for performance and for responding to questions from audition panels. Careful repertoire selection, combined with intensive coaching and close collaboration with a pianist, allowed me to present pieces that suited my voice and highlighted my strengths. Starting the audition with the most challenging piece rather than following chronological order also proved to be an effective strategy.

Ultimately, my goal as a singer is to move an audience. Whether through the hypnotic calm of Purcell, the terror of Schubert’s child, or the playful provocation of Gounod’s Stéphano, I aim to make listeners feel what the characters feel. Can you hear what the Elf King is whispering in my ear? Can you sense the child’s fear, the father’s desperation, the dove’s longing for freedom? If the answer is yes, then the voice has fulfilled its most ancient and powerful function: to communicate emotion directly, across time, language, and style.

Annexes I-IV

Annex I. Musical excerpts

Excerpt 1: Henry Purcell (1659-1695), Music for a while. Sung by Andreas Scholl, countertenor.

Excerpts 2, 3, 4: Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Erlkönig. (different fragments and performers):

2. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, barytone.

The Elf King first tries to attract the child with his sweet talk.

30” Audio file

30 seconds video excerpt: ‘Come, dear child, come along with me!

The games we’ll play will be fine and lovely:

There’s many a bright flower by the water,

Many gold garments has my mother.’

3. Hermann Prey, bass-barytone.

The father tries to calm the child.

Audio file

30 seconds video excerpt: ‘Come, dear child, come along with me!

The games we’ll play will be fine and lovely:

There’s many a bright flower by the water,

Many gold garments has my mother.’

2. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, barytone.

The Elf King first tries to attract the child with his sweet talk.

Audio file

Orchestral version, conducted by James Levine

30 seconds video excerpt: My son, why hide your face, all scared? –

‘Don’t you see, father, the Erlking’s there,

The Alder-King with his crown and robe?’ –

‘My son, it’s the trail of mist that flows’.

()

/

| YouTube video clips | Audio files (Soundcloud) | ||

| 2. | Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, barytone. The Elf King first tries to attract the child with his sweet talk. ‘Come, dear child, come along with me! The games we’ll play will be fine and lovely: There’s many a bright flower by the water, Many gold garments has my mother.’ | https://on.soundcloud.com/xW9gKRpb0kn3VmAKHz | |

| 3. | Hermann Prey, bass-barytone. The father tries to calm the child. ‘My son, why hide your face, all scared? – ‘Don’t you see, father, the Erlking’s there, The Alder-King with his crown and robe?’ – ‘My son, it’s the trail of mist that flows’. (Orchestral version, conducted by James Levine) | ||

| 4. | Jessye Norman, soprano. The child screams, alarmed by the sudden attack of the creature. The narrator tells us the sad end of the story. ‘Father, my father, he’s gripped me at last! The Erlking’s hurting me, holding me fast! ‘– The father shudders, faster he rides, Holding the moaning child so tight, Reaching the house, in fear and dread: But in his arms the child lies dead. | https://on.soundcloud.com/z7Udwc2HFkN7RLZIsr |

5. Charles Gounod (1818-1893): Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle ?, air de Stephano, from Roméo et Juliette. Anat Czarny, mezzosoprano.

https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxlM_K3bpLmWNxkwThLrQPGjdoeh00WUGj?si=Rsq1A14uMHQ13biE

Annex II. Bibliography/sources

- Mithen, Steven. (2005). The singing Neanderthals: The origins of music, language, mind, and body.

- High-pitched voice theory – Neanderthal – BBC science – YouTube

- Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Vocal Studies auditions requirements: https://www.gsmd.ac.uk/study-with-guildhall/music/music-auditions-interviews/vocal-studies-auditions#live-auditions–vocal-studies

- Royal College of Music, Vocal Studies options & auditions requirements https://www.rcm.ac.uk/vocal/auditionrequirements/

- Royal Academy of Music, Vocal Studies audition requirements https://www.ram.ac.uk/study/departments/vocal-studies/audition-requirements

- HENRY PURCELL (1659-1695): Music for a while. Song from the incidental music for Œdipus, King of Thebes Z 583. Scores: https://imslp.org/wiki/Oedipus,_Z.583_(Purcell,_Henry)

- Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_for_a_While

- FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828): Erlkönig, Opus 1, D 328. Scores: https://imslp.org/wiki/Erlkönig,_D.328_(Schubert,_Franz)

- Erlkönig (Schubert) – Wikipedia page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erlkönig_(Schubert)

- Der Erlkönig, poem by Goethe: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erlkönig

- CHARLES GOUNOD (1818-1893): Roméo et Juliette https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roméo_et_Juliette

- Spotify (search and comparison of different versions)

- YouTube ((search and comparison of different versions)

Annex III. Different types of voices singing Music for a While

I did a research on Spotify and YouTube and listened to eleven versions of this song, in nine different keys, spanning from B minor (the lowest) to a 7th higher, A minor, sometimes differing only by half a tone.

| Version | Recording Year | Voice | Key | Comments |

| Henry Purcell original version (1702 edition) | Audio recorded in 1961 by Russell OberlinPurcell: Oedipus, Z. 583: Music For a While | Alto (originally countertenor or boy treble) | C minor | |

| James Bowman | 1995Purcell: Oedipus, Z.583: Music for a While | Countertenor (Alto) | B minor | perhaps it sounds as a B because this recording was made with baroque instruments – A4 was 415Hz, about a semitone lower than today(440Hz)—so they used the original score in Cm. |

| Alfred Deller | 1949: MUSIC FOR A WHILE : ALFRED DELLER : Internet Archive 1979 (in Em)Music For A While | Countertenor (Mezzo) | F minor and E flat minor | (when he was in his thirties in 1949), the oldest recording that I found, surprisingly high. (when he was in his sixties and could not sing so high anymore) |

| Andreas Scholl | 2001 Purcell: Oedipus: Music For A While, Z583 | Countertenor (Mezzo) | E minor | |

| The King’s Singers & J.J. Orlinski | 2020 Music for a while (Purcell) – The King’s Singers & Jakub Józef Orlińskiremotely recorded during the Covid pandemic | A capella choir SAATTBB | E minor | recorded remotely during the Covid pandemic |

| Anne Sofie von Otter | 2004Purcell: Oedipus, Z. 583: Music for a While – YouTube | Mezzosoprano | G flat minor | faster tempo |

| Philippe Jaroussky | 2012 | Countertenor (Sopranist) | G flat minor | |

| Emma Kirkby | 2008Oedipus, King of Thebes, Z. 583: Music for a while | Soprano | G minor | this is the key I chose |

| Carolyn Sampson | 2006Oedipus, King of Thebes, Z. 583: Music for a While – YouTube | Soprano | A flat minor | (Baroque instruments) |

| Sumi Jo | 1995Henry Purcell – Oedipus, Music for a While, Sumi Jo) | Light Soprano | A minor | A lot of vibrato |

Annex IV. Texts and translations

- Music for a while (1692) – Text by John Dryden, from the play ‘Oedipus, King of Thebes’

Music for a while

Shall all your cares beguile.

Wond’ring how your pains were eas’d

And disdaining to be pleas’d

Till Alecto free the dead

From their eternal bands,

Till the snakes drop from her head,

And the whip from out her hands.

Music for a while

Shall all your cares beguile.

- Erlkönig (1815) – Poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, based on the Danish Medieval ballad ‘Elveskud’

| Erlkönig Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind?Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind;Er hat den Knaben wohl in dem Arm,Er faßt ihn sicher, er hält ihn warm. Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?Siehst, Vater, du den Erlkönig nicht?Den Erlenkönig mit Kron’ und Schweif?Mein Sohn, es ist ein Nebelstreif. “Du liebes Kind, komm, geh mit mir!Gar schöne Spiele spiel’ ich mit dir;Manch’ bunte Blumen sind an dem Strand,Meine Mutter hat manch gülden Gewand.” Mein Vater, mein Vater, und hörest du nicht,Was Erlenkönig mir leise verspricht?Sei ruhig, bleibe ruhig, mein Kind;In dürren Blättern säuselt der Wind. “Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn?Meine Töchter sollen dich warten schön;Meine Töchter führen den nächtlichen Reihn,Und wiegen und tanzen und singen dich ein.” Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dortErlkönigs Töchter am düstern Ort?Mein Sohn, mein Sohn, ich seh’ es genau:Es scheinen die alten Weiden so grau. “Ich liebe dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt;Und bist du nicht willig, so brauch’ ich Gewalt.” Mein Vater, mein Vater, jetzt faßt er mich an!Erlkönig hat mir ein Leids getan! Dem Vater grauset’s; er reitet geschwind,Er hält in den Armen das ächzende Kind,Erreicht den Hof mit Mühe und Not;In seinen Armen, das Kind war tot. | The Elf King – English translation Who rides so late through the wind and night?It’s a father with his child so light:He clasps the boy close in his arms,Holds him fast, and keeps him warm. ‘My son, why hide your face, all scared? –‘Don’t you see, father, the Erlking’s there,The Alder-King with his crown and robe?’ –‘My son, it’s the trail of mist that flows’. – ‘Come, dear child, come along with me!The games we’ll play will be fine and lovely:There’s many a bright flower by the water,Many gold garments has my mother.’ ‘And father, my father, can’t you hearWhat the Erlking’s whispering in my ear?’ –‘Peace, peace, my child, you’re listeningTo those dry leaves rustling in the wind.’- ‘Fine lad, won’t you come along with me?My lovely daughters your slaves shall be:My daughters dance every night, and theyWill rock you, sing you, dance you away.’ ‘And father, my father, can’t you see whereThe Erlking’s daughters stand shadowy there? ‘My son, my son, I can see them plain:It’s the ancient willow-trees shining grey.’ ‘I love you, I’m charmed by your lovely form:And if you’re not willing, I’ll have to use force.’ ‘Father, my father, he’s gripped me at last!The Erlking’s hurting me, holding me fast! – The father shudders, faster he rides,Holding the moaning child so tight,Reaching the house, in fear and dread:But in his arms the child lies dead. |

- Roméo et Juliette « Depuis hier… Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle ? (Qui vivra verra)» (1867) French libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, based on Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet. Although most of the libretto follows closely the original, Stephano’s character was newly written for the opera.

| « Depuis hier… Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle ? » recitativoDepuis hier je cherche en vain mon maître !Est-il encore chez vous, messeigneurs Capulet? Voyons un peu si vos dignes valets à ma voix ce matin oseront reparaître. ariaQue fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Dans ce nid de vautours? Quelque jour, déployant ton aile Tu suivras les amours! Aux vautours, il faut la bataille; Pour frapper d’estoc et de taille Leurs becs sont aiguisés! Laisse là ces oiseaux de proie Tourterelle, qui fais ta joie Des amoureux baisers! Gardez bien la belle! Qui vivra verra! Votre tourterelle vous échappera. Un ramier, loin du vеrt bocage Par l’amour attiré A l’entour de cе nid sauvage A, je crois, soupiré! Les vautours sont à la curée Leurs chansons, que fuit Cythérée Résonnent à grand bruit! Cependant, en leur douce ivresse Nos amants content leur tendresse Aux astres de la nuit! Gardez bien la belle! (…) | « What are you doing, White Dove?” – English translation Since yesterday I have been searching in vain for my master! Is he still at your place, my lords Capulet? Let’s see if your worthy servants this morning will dare to reappear at my voice. What are you doing, white dove, In this nest of vultures? One day, spreading your wings, You will follow love! Against vultures, battle is necessary, To strike with thrust and cut, Their beaks are sharp! Leave these birds of prey, Dove who finds joy In lovers’ kisses! Take care of the beauty! Who lives will see! Your dove will escape you, A wood pigeon, far from the green grove, Attracted by love, Around this wild nest I believe, sighed! The vultures are feasting, Their songs, which Cytherea flees, Resound loudly! Meanwhile, in their sweet intoxication, Lovers share their tenderness With the stars of the night! Take care of the beauty! (…) |

Bonus version

This is a semi-staged performance with four singers, one of them a young child. It’s not as vocally impressive as the previous ones, and the child is not expressive enough, but it makes dramatic sense and highlights the diffficulty of singing the whole song with the same voice.

Leave a Reply